Before the Democratic Reform in 1959, Tibet had long been a society of feudal serfdom featuring the despotic temporal and religious administration. As the head of the Gelug Sect of Tibetan Buddhism, the 14th Dalai Lama served as the head of the local government of Tibet, holding both the political and religious power at the same time. He is therefore the chief representative of this feudal serfdom. Tibet's three major estate-holders--local administrative officials, nobles and upper-ranking lamas in monasteries, and their agents, accounted for less than 5 percent of Tibet's population, but owned most of Tibet's means of production. However, serfs and slaves, who made up over 95 percent of Tibet’s population, owned no means of production and enjoyed no personal freedom. Serf-owners had a firm grip on the birth, death and marriage of serfs and slaves. They could freely sell and buy, and transfer slaves and serfs, and could also exchange slaves and serfs with other slave-owners, and pay a debt with slaves and serfs. Serf-owners and major monasteries in Tibet established prisons of their own, and tortured inmates in a savage way. Statistics show, before 1959, the clan of the 14th Dalai Lama owned 27 manors, 30 pastures and some 6,000 slaves and serfs to till the land and herd livestock for them. The 13-Article Code and 16-Article Code, which were enforced in old Tibet, divided hgbfvdeswabody, while the lives of people of the lowest rank of the lower class are worth a straw rope.

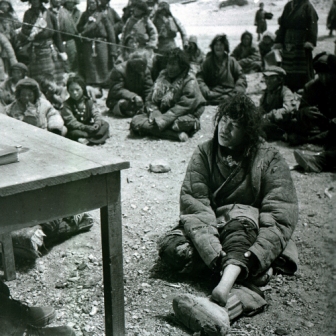

Photo 2-1-E

In the picture is a statistical table on the properties of the 14th Dalai Lama and his clan.

Before 1959 Tibet followed the feudal serfdom featuring temporal and religious administration. The society was tightly controlled by the high-ranking monk and lay officials, and the slave-owners (officials, high lamas and nobles). The Dalai Lama was religious leader and also the largest slave-owner. Before the Democratic Reform in 1959, he and his clan owned 27 manors, 30 pastures and some 6,000 slaves and serfs. Each year, they collected 33,000 ke (each ke equal to 14 kg) of qingke highland barley, some 2,500 ke of butter, 300 head of cows and sheep, 175 rolls of pulu woolen fabrics, and more than 2 million tales of Tibetan silver from their slaves and serfs engaged in farming and livestock breeding. And the Dalai Lama himself alone owned some 10,000 pieces of silk, high-grade woolen and fur garments, including some 100 cloaks adorned with gems and other precious stones. Up till 1959, he owned more than 160,000 tales of gold, 95 million tales of silver and more than 20,000 pieces of jewelry.

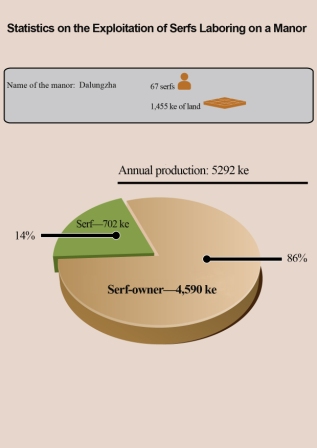

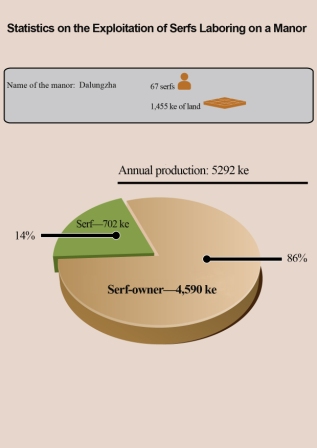

Photo 2-2-E

Picture shows the exploitation of serfs and slaves in a manor.

Before the Democratic Reform in 1959, Tibet had long been a society of feudal serfdom featuring the despotic temporal and religious administration, a society which was darker and more cruel than the European serfdom of the Middle Ages. Statistics show Tibet's three major estate-holders--officials, nobles and upper-ranking lamas in monasteries, and their agents, accounted for less than 5 percent of Tibet's population, but owned most of Tibet's means of production. The three major monasteries (the Sera, Gandain and Zhaibung Monasteries) in Lhasa, for instance, owned 321 manors, 147,000 ke (15 ke equal to one hectare) of land, 26 pastures and some 40,000 slaves and serfs.

Photo 2-3-E

Picture tells the legal codes of old Tibet divided the Tibetans into three classes and nine ranks.

In order to safeguard the interests of serf-owners, Tibetan local rulers formulated a series of laws. The 13-Article Code and the 16-Article Code, which were enforced in old Tibet for several hundred years, divided people into three classes and nine ranks. They clearly stipulated that people were unequal in legal status. The standards for measuring punishment and the methods for dealing with people of different classes and ranks who violated the same criminal law were quite different. In the law concerning the penalty for murder, it was written, "As people are divided into different classes and ranks, the value of a life correspondingly differs." The lives of people of the highest rank of the upper class, such as a prince or Grand Living Buddha, are calculated in gold to the same weight as the dead body. The lives of people of the lowest rank of the lower class, such as women, butchers, hunters and craftsmen, are worth a straw rope. Under the rampart of the institutionalized rigid hierarchy, the inequality between the rulers and the ruled people and between the exploiters and exploitees was further strengthened in terms of the economic and political status. Moreover, this kind of inequality was even showed in every detail of daily life and a noun or a verb in the speech.

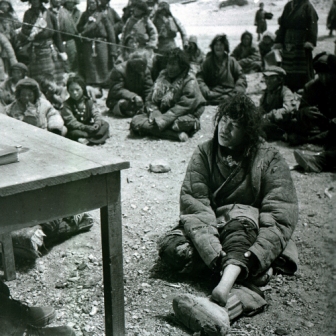

Photo 2-4

Picture shows serf holding the newborn baby went to pay tax to and get the baby registered with the serf-owner.

In old Tibet which followed the feudal serfdom featuring temporal and religious administration, the three estate-holders owned most of the means of production and, through economic means, owned slaves and serfs. Gashag, the local government of Tibet, stipulated that serfs were not allowed to leave at will the manors they belonged to; they were banned to flee. Serfs and slaves, making up 95 percent of the Tibetan population, were attached to land and subject to the three estate-holders. They enjoyed no personal freedom at all. Serf-owners had a firm grip on the birth, death and marriage of serfs. They could freely sell and buy, and transfer slaves and serfs, and could also exchange slaves and serfs with other slave-owners, and pay a debt with slaves and serfs. Children of serfs were registered the moment they were born, setting their life-long fate as serfs. After death, the names of serfs were written off from the book held by their owners. Male and female serfs not belonging to the same owner had to pay "redemption fees" before they could marry. Newborn babies of serfs had to pay “birth tax” and got registered with the owners their parents belonged to; this means they would be lifelong serfs of the owners in future too. When serfs were forced to make a living in other places, they had to pay tax; they would not be taken as the fugitive only when they could show paper certifying they had paid tax for this. This fully shows the serfs enjoyed no personal freedom at all, let alone dignity.

Photo 2-5

Picture shows the serf carrying his serf owner, a kind of Ula corvee.

Serf-owners ruthlessly exploited serfs through corvee and usury. Incomplete statistics indicate the existence of more than 200 categories of corvee taxes levied by the Gaxag (Tibetan local government). The corvee assigned by Gaxag and manorial lords accounted for over 50 percent of the labor of serf households, and could go as high as 70-80 percent. Ula corvee is the principal form in which the three major estate-holders ruthlessly exploited the serfs in old Tibet under feudal serfdom. Ula corvee is a general term for various corvee, taxes and ground rent in a broad sense. These corvee labor and taxes brought serfs heavy burden. Despite industrious labor year after year and month after month, they had no enough food to live on. Permanent corvee tax was registered and there were also temporary additional corvee taxes. The corvee tax was divided into “inside” and “outside” ones in form. The former refers to various forced labor and materials that serfs should pay to the aristocrats, or upper-ranking monks, and monasteries and their agents. The three major estate-holders could levy corvee and taxes on their serfs at will as long as they needed. There was no explicit provision as to how many corvee taxes the serfs would pay, which was determined by the estate-holders. In this way, serfs spent two-thirds, even three-fourths time of a year offering free corvee labor for their estate-holders. The “outside” one refers to the corvee and taxes that serfs paid to the Gaxag (Tibetan local government). Serfs needed to carry the officials, monks, businessmen and soldiers holding the tokens given by the Gaxag, and their materials free with man power or animal power, lodge them free, construct some projects launched by the Gaxag and monasteries free, and pay some materials such as highland barley, butter and eggs and money such as silver dollars and Tibetan silver that the Gaxag needed.

Photo 2-6

Picture shows serf-owners forced their serfs to do labor while being shackled.

In old Tibet, the level of the productive forces was very low, the farm tools were primitive with wooden plow, wooden hoe or iron-plowshare wooden plough still used in main agricultural areas, and grain yield was only four to five times the seeds sown.

Photo 2-7

Picture shows a nangzan serf named Cering Zholma living under a toilet.

Serfs made up 90 percent of old Tibet’s population. They were called tralpa in Tibetan (namely people who tilled plots of land assigned to them and had to provide corvee labor for the serf-owners) and duiqoin (small households with chimneys emitting smoke). They had no land or personal freedom, and the survival of each of them depended on an estate-holder’s manor. In addition, nangzan who comprised 5 percent of the population were hereditary household slaves, deprived of any means of production and personal freedom. Nangzan means “domesticated” slaveries. They were viewed as the “speaking beast” by the serf-owners.

Photo 2-8

Picture shows a stamped official document about monastery “Lharang” sending serfs Cering Dorje, Kumsang (female), and Sumpotri (female) to the Chawo residence palace as servants.

Serf-owners literally possessed the living bodies of their serfs. Since serfs were at their disposal as their private property, they could trade and transfer them, present them as gifts, make them mortgages for a debt and exchange them. According to historical records, in 1943 the aristocrat Chengmoim Norbu Wanggyai sold 100 serfs to a monk official at Garzhol Kamsa, in Zhikung area, at the cost of 60 taels of Tibetan silver (about four silver dollars) per serf. He also sent 400 serfs to the Gundeling Monastery as mortgage for a debt of 3,000 pin Tibetan silver (about 10,000 silver dollars).

Photo 2- 9

Picture shows a slum called Pangcun in Lhasa, which was home to beggars.

Before the Democratic Reform in Tibet in 1959, Lhasa’s downtown area had a population of some 20,000. It was surrounded by some 1,000 tattered tents, homes of poverty-stricken people and beggars. The average life expectancy was only 35.5 years in old Tibet in 1951. In old Tibet there was not a single school in the modern sense. The enrollment rate of school-age children was less than 2 percent, and the illiteracy rate reached 95 percent.

Photo 2-10

In the picture, one foot of a herder named Duito in Amdo County was chopped off by the tribal chief.

The interests of the three major estate-holders were sacred and inviolable in the codes. If the serfs encroached upon the interests of the three major estate-holders, it was regulated in the codes that “such punishments as gouging out the eyes, paring the leg meat, cutting off tongue and hands, pushing people from the cliff, throwing people into water or killing the person would be conducted to the violators in accordance with the different offence as a warning to others”. However, the rights and interests of the broad masses of serfs and slaves were not at all guaranteed in the codes; and it was illegal for the serfs and slaves to cry out their grievances. The codes stipulated, “Anyone who voices grievances at the palace, behaving disgracefully, should be arrested and whipped”; “anyone who resists a master's control should be arrested”; “anyone who spied the important matter should be arrested”; and “a commoner who offends an official should be arrested”. It was also stipulated that a servant who seriously injured his master should have his hands or feet chopped off; a master who injured a servant was only responsible for the medical treatment for the wound, with no other compensation required. The one who injured a Living Buddha committed a felony and should have eyes gouged out, feet and hands chopped off or be executed in various ways. It was just these appalling stipulations that made the three major manorial lords conduct varied atrocities on the serfs and slaves at their pleasure.

Photo 2-11

Picture shows herder Pemo Hongchin shoes right hand was chopped off by the serf-owner.

Making use of written or common law, the serf-owners set up private jails. Local governments had law courts and prisons, as had large monasteries. Estate-holders could build private prisons on their own manor ground. Punishments were extremely savage and cruel, and included gouging out the eyes; cutting off ears, hands and feet; pulling out tendons; and throwing people into water. Many materials and photos showing limbs of serfs mutilated by serf-owners in those years are kept in the Tibetan Social and Historical Relics Exhibition in the Beijing Ethnic Cultural Palace.

Photo 2-12

Picture shows the skins of people decorticated by a serf-owner.

The monasteries formulated special “regulations” and the nobles the detailed “domestic laws” in their own manors according to the codes. Both the monasteries and nobles could use instruments of torture and set up law courts privately to punish the serfs and slaves and even put them to death. The late 10th Panchen Erdeni said when he received the interview of a reporter from the magazine National Unity, “Before the Democratic Reform in 1959 Tibet had long been a society of feudal serfdom under the despotic religion-political rule of lamas and nobles, a society which was darker and more cruel than the European serfdom of the Middle Ages.” In the Gandain Monastery, one of the largest in Tibet, there were many handcuffs, fetters, clubs and other cruel instruments of torture used for gouging out eyes and ripping out tendons. A letter to Rabodian chief in the early 1950s kept in the Tibet Autonomous Region Archive bore witness to this. It said, “In order to celebrate the birthday of the Dalai Lama, all the members of the Lower Tantric Institute should chant the script. To practically complete this Buddhist service, one wet intestine, two skulls, various kinds of blood and a whole piece of the skin of a person are required urgently. You’d better bring them here as soon as possible.”